In my free time, I’ve been reading Great Streets, the 1995 urban design art book, by Allan Jacobs — and a great birthday present from Honey :). Jacobs dedicates an entire chapter of Great Streets to Venice’s Grand Canal, making the case that certain cities’ urban canals are essentially liquid streets: as thoroughfares, places for public gathering, retail business, the showcasing of architecture, and cross-cutting neighborhood vistas.

In my free time, I’ve been reading Great Streets, the 1995 urban design art book, by Allan Jacobs — and a great birthday present from Honey :). Jacobs dedicates an entire chapter of Great Streets to Venice’s Grand Canal, making the case that certain cities’ urban canals are essentially liquid streets: as thoroughfares, places for public gathering, retail business, the showcasing of architecture, and cross-cutting neighborhood vistas.

Now, Google seems to have taken Jacobs’s position, offering extensive and striking StreetView images of the canals of Venice, treating them as the equivalent of city streets. Here’s a view of the Grand Canal, near the Rialto Bridge:

Here’s the Campanile di San Marco, seen from the water:

And here is a satellite view of the entire old city, surrounded by the Lagoon.

It’s fitting that the outline of Venice looks like a fish.

Now, in some ways, the canals of Venice are more than just technically streets. One could argue that in light of the role Venice played in the emergence of the modern commercial world the patterns of urbanization that developed there actually served as an early prototype for the growth of modern cities. The traffic flows in the city’s canals were not so different from those of land vehicles in modern or ancient cities. But the liquid nature of these streets presumably allowed for one less break of bulk between the arrival of goods in the city and their delivery to local end users — and this was good for the productive economy. In Roman Ostia, vast warehouses were used to store shipments of olive oil and wine amphorae that had been imported from Africa, Greece, and Spain. Each shipping company had its own branded warehouse, from which it sold goods to merchants one step down the supply chain, or stored them until its own distributors were ready to take them to market. Much smaller quantities were then transported, separately, up the Tiber to the city proper; or over land to other Italian cities and towns. This made for a supply chain with a lot of middle men, barriers to purchasing in bulk, and, presumably, high markups between the seaport and Roman workshops.

In Venice, the innovation would be that these points of delivery could be distributed throughout the city, rather than concentrated in a single seaport. In Venice, the urban fabric and the seaport became one, a development that predicted the more distributed pattern of industrial space in modern cities. Canals and their branches and slips would, of course, continue to be an important part of city-building for years to come, but only a few cities would have both the topography and trading frequency to justify the kind of extensive canal building that took place in Venice. Amsterdam comes to mind. More commonly, the post-Renaissance economy would interpret the lesson from Venice in another way: The most successful cities to be founded after the Renaissance would be those built on sites where natural waterways conveyed an almost Venetian advantage, and allowed for distributed delivery points. Think of New York City, with its miles and miles of natural waterfronts. Likewise, Hong Kong, San Francisco, and Sydney. Finally, the pattern of distributed industry would really be broken open, in the 19th century, by the railroads, which would slice through the fabric of every European and American town and city as thoroughly as the canals sliced through Venice.

Another interesting point is that Venice is also arguably more of a direct continuation of the Roman tradition than Byzantium was. That is to say, while the Eastern Empire may have carried on the apparatus of the Roman state from Constantinople until 1453, is was essentially a Greek cultural entity for its entire history; but Venice was founded in the fifth century by Italian Romans who had taken refuge from the fall of the Western Empire in an inaccessible Italian swamp, and who went on to preserve a slice of distinctly Latin culture — eventually building a city that carried on many parts of the Italian Roman tradition, and served as a unique cultural bridge between Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages and, ultimately, the Early Modern age. This is a simplification of Venetian history, but it illustrates the important thread. Because the plan of Venice — and especially its canals — more literally captures the tradition of Western commercial cities growing out of the sea, than almost any other example of European urbanism. From Ostia to Venice, and from Amsterdam to New Orleans, the mercantile tradition in the West has a long tradition of shaping a maritime urbanism in which the riches brought by sea trade have driven extensive urban growth on the land around the ports. And this growth has always been premised on the trading patterns of the merchants within the seaports.

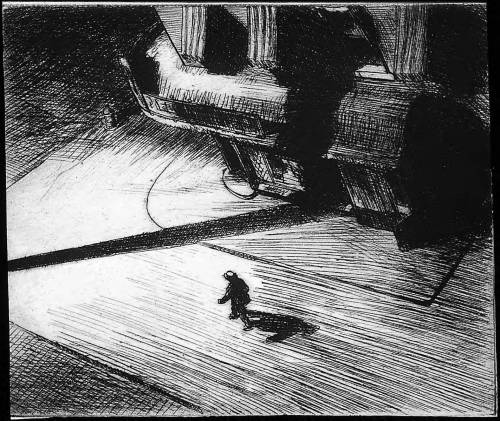

The sea has always been a saturating element in trading cultures. Look at the Odyssey. Look at its haunting omnipresence in this Roman wall painting of Perseus and Andromeda, on view at the Metropolitan Museum, found in Boscotrecase, near Pompeii:

Perseus and Andromeda, from the Villa at Boscotrecase. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Amidst its clear references to religion and fantasy, it is the sea, and not Vesuvius, which might consume all. I thought of this painting recently at work, where I’m writing decision letters for a post-Sandy recovery project here in New York City. Three years after that storm, the conflict between the city and the ocean is still being sorted out, block by block, house by house. Some people are selling their land back to the state; some are elevating their homes, with or without public subsidies; many are keeping their fingers crossed and going on as if nothing had happened in 2012.

The same forces of commerce, greed, politics, and ambition that built the world’s port cities are now driving the global climate change that threatens them. New Orleans was nearly wiped out in 2005; Venice now deals with flooding on a regular basis; in New York, Manhattan seems mostly oblivious, but the sprawling coastal neighborhoods of the outer boroughs are not looking very healthy. The paradox of mercantile cities, the wealth that they draw from maritime trade, and the ever-present danger of the sea, will not go away. It is only getting stronger.

Read Full Post »

In a Times piece called “

In a Times piece called “ In my free time, I’ve been reading

In my free time, I’ve been reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.